By Emily Beck and Kaylee Morlan

COVID-19 has brought all of the bakers out of the woodwork. From sourdough to elaborately-decorated focaccia, many people are lifting their spirits with yeast, baking powder, and baking soda. Not to be left behind, we in the Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine (WHL) decided to follow suit, but in an appropriately historical manner.

In 2015, Assistant Curator Emily Beck and student employee Sarah Juntunen made “Portugal Cakes” from an 1820 English recipe manuscript that the WHL owns. Five years later, and with campus shut down, Emily and Kaylee Morlan, WHL student employee and U of M History student, decided to embark upon another historical cooking endeavor.

Selecting a recipe

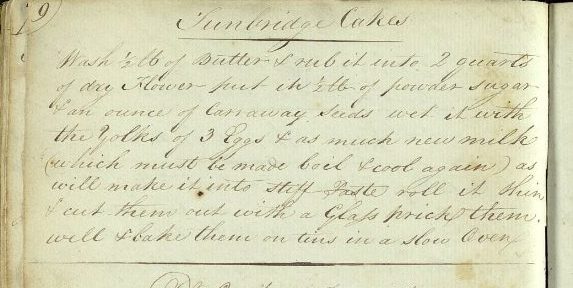

The recipe we landed on was for “Tunbridge Cakes” from a late 18th-century manuscript recipe book from the WHL. We had never heard of Tunbridge Cakes, but we had (mostly) correct ingredients at home already, and willing judges (our partners) to tell us how we did. Read on below to see how our historical bakes turned out.

Making adjustments

First, we gathered up all of our ingredients. The recipe calls for butter, flour, powdered sugar, caraway seeds, eggs, and “new milk.” Kaylee didn’t have any caraway seeds, so replaced them with cumin seeds. Neither of us have access to “new milk,” so we just used the 1% from our fridges.

Kaylee’s ingredients are on the left, and Emily’s are on the right.

The recipe seemed quite large, and both of us decided to halve it. Kaylee did some extra research on 18th century baking measurements to see if any measurements used that are familiar to us today were completely different at the time. The research she did led her to Paula Walton’s 18th Century Home Journal, which proved a much better resource for ingredient amounts than the measurement converter on Google.

Interpreting the recipe

After the dough was mixed together, we rolled it out. The recipe says to “roll [the dough] thin,” which we both decided was probably around a quarter of an inch thick. We still aren’t sure how thick they should have been.

Kaylee’s dough is on the left, and Emily’s is on the right

After cutting the dough in circles with a glass, we placed them on a “baking tin,” “pricked them well,” and baked them in a “slow oven.”

Kaylee’s Tunbridge Cakes are baking on sheet pans in the oven. Emily’s Tunbridge Cakes are waiting to be baked on a sheet pan.

Kaylee baked her cakes at 300 F for 20 minutes, then 350 for 20 minutes. Emily baked hers at 325, but can’t remember for how long… “until they were done.”

Final taste test

How did they turn out? The texture of the cakes — which was more like a dry biscuit than a cake — was pretty good. They’d be nice for dunking into a cup of tea. The flavor of caraway and cumin in a sweet baked good, though, was surprising for us. As a good Midwesterner, Emily is more used to caraway in sauerkraut than in a cookie. We did agree that it is fun to experience what flavors people in the past enjoyed, even if they may seem surprising to us today.

Kaylee’s Tunbridge Cakes are on the left, Emily’s are on the right.

What did our guest judges think? Kaylee’s ranked 19/20, and Emily’s ranked 18/20, but they may have just been being kind to us (after all, they have to stay on our good side while we’re quarantined together). Emily delivered a few Tunbridge Cakes to a friend who said, “I don’t want to offend you, but… you can tell that these came from an historical recipe. They aren’t bad, though!”

Try them out yourself at home and let us know what you think!

Wash ½ lb of butter & rub it into 2 quarts of dry flower put in ½ lb of powder sugar & an ounce of Carraway seeds wet it with the yolks of 3 eggs & as much new milk (which must be made boil and cool again) as will make it into stiff paste roll it thin & cut them out with a glass prick them well & bake them on tins in a slow oven.

Available online through UMedia: Mrs Keyworth, English medicinal and cookery receipts, c. 1795-1816. Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine, WZ260 E58 1795 (page 27).

About the authors

Emily Beck, Ph.D. is the Assistant Curator of the Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine. One of her research specialties is the history of recipes in premodern Europe, so cooking from the Wangensteen’s recipe collections is one of her favorite things to do.

Kaylee Morlan is starting her final year as a history major at the University of Minnesota in the fall of 2020, and has been working as a student employee at the WHL since the fall of 2018. She wouldn’t have considered herself much of a baker in the past, but the start of quarantine gave her the time to practice and take up baking as a newfound hobby!

It’s Ye Olde, not Yea Olde. “Ye” = “you”, or “the”. “Yea” =” Yes”, or sometimes “very”. The sense Ye = The is the meaning wanted here. Thanks for the recipe.

Thanks for catching this. I’ve made the correction.

Excellent idea to pull out old recipes and try them anew.

I’m wondering if these were ones we used to make in rural Vermont as a child, since there is a Tunbridge Vermont (with the Tunbridge World’s Fair each year)?

They are very much like the typical Vermont Crackers, made in Westminster, Vermont – flaky and very dry but biscuits that would store forever in tightly closed metal tins.

A great project. I was a bit stunned to see that anyone would simply substitute cumin seeds for caraway seeds, though– they may LOOK similar, but could hardly taste more different! Caraway seeds seem like a strange choice to us moderns, but they were the “seed” in “seed cake,” a teatime stalwart mentioned in countless British novels of the Victorian era and before. Seed cake almost seemed to be shorthand for “old-fashioned” in later eras. There are lots of seed cake recipes available– a dense, not too sweet sort of pound cake. It’s interesting to taste caraway outside of rye bread or sauerkraut, but having made it once, I probably won’t again. I’d say it’s pretty much a soft, cake version of these seed biscuits. Here’s Mrs. Beeton’s recipe : http://www.mrsbeeton.com/35-chapter35.html

What a wonderful experiment! It sounds like the cakes were meant to be dunked in tea-terrific history thanks Emily, Kaylee and Mark.