Students in Dominique Tobbell’s Technology and Medicine in Modern America class had a unique opportunity to place contemporary issues in medicine and health care in their historical context.

We are pleased to present the last in a three-part series showcasing the work of Tobbell’s students as we take a closer look at prosthetic limbs through the work of U of M senior Paige Lasota.

Lasota’s research was shaped by artifacts and primary source materials found at the Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine, which set the groundwork for discovering how prosthetic limbs were used in the past and how their history has shaped contemporary practice.

Prosthetic Limbs: Disability Discrimination and Concealment in the 18th Century to the Present

By Paige Lasota

“A woman has revealed she was REJECTED from 100 jobs — until she applied for a role and left her disability off her covering letter” (1).

Shani Dhanda was looking for a part time job while studying in college in the early 2000s. She applied for over 100 jobs using a cover letter that disclosed her disability of Osteogenesis imperfecta. She did not hear back about any of the vacancies. Once she removed her condition from the cover letter, a company offered an interview.

History repeats itself

This isn’t the first time people with disabilities have faced doubt and discrimination or felt the need to hide their disability. When returning home from the American Civil War, veteran amputees struggled to prove their capabilities. The Industrial age and the Civil War were the biggest factors for severed limbs in America.

Fly-wheels, pulleys, railroads, and new weapon technology left many working men and veterans in need of prosthetics. “Most destructive was the Civil War, which marked the first sustained use of accurate, breech loading firearms. They usually shattered two to three inches of bone, and carried bits of skin and clothing. Doctors usually opted to amputate the limb,” (2) states Stephen Mihm, a historian of disability.

Prosthetics in the 18th century

Figure 1 from: “Artificial limbs” by Heather Biggs (1885) (3), available at the Wangensteen Historical Library.

Prosthetic legs, known as artificial limbs, were quite simple in the mid 18th century. They were made of heavy wood and leather. Heather Biggs, a surgeon in 1885 explained the simplistic design. “[The mechanic] only copied vaguely by the light of external structure” (3). Bigg’s drawing shows the limb that resembles the shape of a human leg (figure 1).

Amputees in early 19th century America

John Rees, a resident of New York in 1913, called amputees “indigent cripples” (4) in an opinion article. He said amputees resided and begged on the streets. Rees urged them to go to organizations, such as New York’s Cripples Welfare Society. They provided artificial limbs and helped find jobs. People perceived amputees as dependent on charity and only productive if they had prosthetics.

Post-war disability: A battle for rights

Proving their capabilities was still a struggle for veteran amputees after World War II. Yet, as the disability movement began, amputees took things into their own hands. The National Amputation Foundation arranged a baseball game between World War II Amputee Vets and “Al Schacht’s Broadway-Hollywood All-Stars” in 1950.

The game aimed to prove that veterans with disabilities are capable of working a job. It showcased how prosthetics enabled and empowered amputees. A newspaper article told stories of the players. “Bob Anderson, amputee team captain, 27 years old, who lost his left arm in the Battle of the Bulge and who now owns a prosperous trucking business” (5).

Hiding what’s already lost

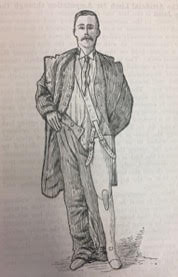

Figure 2 from: “Engineering masculinity” (2002) (6).

During and after World War II, advancements continued as demand increased for prosthetics. The prosthetic’s main function is to restore function and productivity. But technological advancements served another purpose: concealing disability.

Men who came back from the war failed to fit into their previous roles, dubbed as “ineffective” and “disabled.” As prosthetics became easier to use and access, the easier it was to hide or make up for a missing limb and maintain an identity of able-bodied. Figure 2 (right) is an example of an advertisement for prosthetics geared towards veterans. Advertisements showed “veteran amputees using new prosthetic devices to perform ‘normal’ male activities” (6).

Embracing disability

Nowadays, society is slowly accepting and embracing people of all abilities. Individuals feel more empowered to present their differences. Leslie Smith had her left leg amputated while serving in the army. A decade later, she proudly walked the Project Runway’s catwalk with her prosthetic leg (7).

Felicia Cantone had her leg amputated due to bone cancer and wore a prosthetic leg for years. Now she has stopped using it. “‘I wanted to show people who I really am, I was tired of hiding my leg in pictures and feeling forced to wear a prosthetic every day” (8).

People with disabilities can choose to use assistive technology or not. They can choose whether to conceal their disability. But, people with disabilities should not have to hide or correct their disability. Society and employers should welcome and accommodate people with disabilities.

About the author

About the author

Paige LaSota is a senior at the University of Minnesota majoring in An Exploration of the Social Construction of Dis/Ability and its Implications. She is interested in how various medical technologies reinforce perceptions of disabilities. Paige loved working hands-on with artifacts, such as the prosthetic leg, in HMED 3075: Technology and Medicine in Modern America.

Works cited

- Stephanie Balloo. “Woman REJECTED from over 100 jobs – until she removed disability from application.” BirminghamLive (London), Nov 7, 2017.

- Stephen Mihm. A limb which shall be presentable in polite society: Prosthetic technologies in the nineteenth century. New York: University Press, 2002.

- Biggs, Heather. Artificial limbs, and the amputations which afford the most appropriate stumps in civil and military surgery. London: Self-published, 1885.

- Rees, John. “Welfare Society Provides Artificial Limbs and Employment.” New York Times (New York, N.Y.), Sep 7, 1913.

- “War Veteran Amputees to Play Baseball To Show They Can Fit Into Normal Jobs.” New York Times (New York, N.Y.), Jul 9, 1950.

- David Serlin. Engineering masculinity: veterans and prosthetics after World War II. New York: University Press, 2002.

- “Female U.S. Army veteran with prosthetic leg proudly hits the catwalk in five-inch heels on Project Runway All Stars.” DailyMail (London), Jan 7, 2013.

- Nicole Morley. “Teen ditches prosthetic leg after a decade of hiding her disability.” Metro (London), March 18, 2017.