By Laurie Jedamus

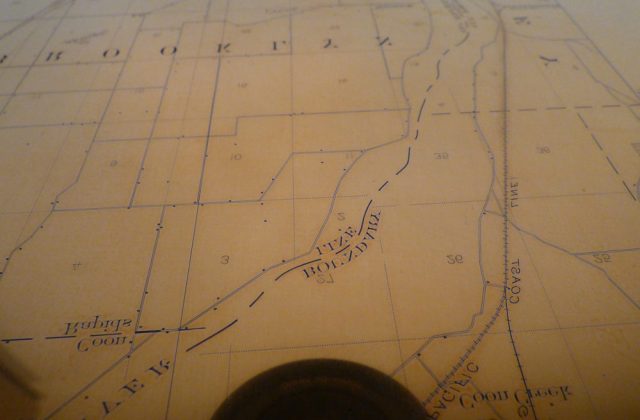

Collections Management and Preservation is working on a fascinating project for the John R. Borchert Map Library: We’re cleaning and preparing for display a collection of 36 copper plates that were used to print United States Geological Survey (USGS) maps. The plates in the collection will be on display in an exhibit at Elmer L. Andersen Library from February 13 through May 27.

Each plate is made of solid copper, measures 17 inches by 21 inches, and weighs 14 pounds! All are covered with a variety of substances that include decades-old ink, grease pencil, and general corrosion. We’re removing all these substances to keep them from further damaging the plates, and also to make the plates more user-friendly for an upcoming exhibit.

The USGS owned thousands of these plates, and decommissioned them decades ago when newer technologies came in. When they recently decided not to continue storing them, they made them available to public and nonprofit institutions, including the Borchert Map Library. Plates that remained were then auctioned off to the general public — you can occasionally still find one available online, but most have found homes.

Conservation challenges for copper plates

Our plates were used from the 1880s to the 1950s to print maps of different areas in Minnesota. Lines were engraved into each plate, with separate plates for topographic features, water features, and man-made features for a particular area of Minnesota. Images from the three different types of plates were used for each map, using a different color of ink for each type of information.

Since our expertise is primarily with paper-based materials, it was challenging to find the best way to clean the plates. Our background research included books about the intaglio printing process and conversations with local fine arts printers. They were useful for general background and for advice on the best way to store the plates, but of limited help with advice on cleaning off decades-old ink, since printing plates are usually meticulously cleaned immediately after each use.

Our main resource was conservators. Tom Braun, the objects curator at the Minnesota History Center, has been amazingly helpful. He’s given us advice throughout the project, and has suggested cleaning agents, techniques, and tools to use and avoid. We also posted on Conservation OnLine’s Conservation DistList, a weekly online publication for conservators and people in related fields, which provided some very interesting and helpful suggestions. We even got advice from a conservator at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, who had been working on a similar project involving copper plates used for etchings.

We learned that many common cleaning processes and materials should be avoided because of their potential for damaging the plates. We ruled out using mild acids (like lemon juice), as well as abrasive scrubbers that clean quickly but can also scratch (copper is surprisingly soft, about 2.5 on the Mohs scale, about the same as gold.). Other substances like ammonia that clean well, but have unwanted side effects like changing the color of the copper to an odd pinkish color, were also ruled out.

Our basic process, arrived at after advice from the conservators supplemented by considerable experimentation, relies on multiple cleaning agents ranging from Dawn dish soap to Vaseline, materials including homemade scrubbing blocks made from bookboard scraps and paper towels (surprisingly, they work better than more expensive options), and especially, a lot of elbow grease.

As the plates are cleaned, we are housing them in custom–made enclosures. When it comes time to exhibit them, since the very fine engraved lines are difficult to see once the plates are cleaned, the plates will have very finely powdered charcoal buffed into the lines — an easily reversible way to make them more visible.

I’m a French and German trained Printmaker in Los Angeles, and for a Client I print these same Plates. The most used material to protect the Plates is shellack, made from shellack flakes dissolved in Methyl Alkohol. To remove it, place the copper plate on a handwarm hotplate and after 20 min or so, use a soft terrycloth with Turpentine to remove the old hardened sheelack. Some Plates have what the old french called Rouge under neath the shellack, make a paste from Flour and water and plenty of ellbow grease to remove it.

Thanks for the useful information! I’ll add it to our project files.

And Btw, they are etched, only mistakes were corected by pushing up the copper, polishing it and than engrave the corections in.

this is absolutely fascinating to say the least! I happened upon what I believe are also copper plates, as they are all images of areas in the Dubuque, Iowa Masonic Temple ( of which I am a member of Mosaic Lodge 125), as well as many portraits. I would love to be able to restore ours as well, plus once they are restored I would like to try to scan them to share them digitally as well, especially since next year our Grand Lodge is celebrating our 175th year.

I’d be happy to talk with you about your copper plates! I’ll contact you offline.

Laurie,

I read with great interest the description about restoring copper plates. I represent a group called “The Tin Whistles”. We are the oldest active Golf Society in the US, based in Pinehurst NC. We were formed in 1904 and serve as a charitable organization, giving out hundreds of thousands of dollars in college scholarships to area students as well as promoting the game of golf. We recently acquired a copper plate display listing the winners of our annual Golfing Championship from the early 1900’s. It was very tarnished and unreadable. An attempt was made to clean it but to no avail. Regrettably, it is nearly impossible to read the names and dates, with the engraving being so finely made. (Your description of the buffed powdered charcoal sounds like a perfect solution!) Can you direct me to any conservator who may be willing to examine our plaque and give us an idea of how it might be restored? I await your reply.

Roger Castanien

I have meanwhile clened over 100 of this Plates, as I’m also able to print from them and create a 3 color print.

Hello! I’d love to learn more about the custom housings you made for these plates. I work in a University Library as well and am tasked with rehousing some of our own. Many thanks!